In the previous newsletter I briefly expanded on the notion that we are commonly brought up having misinformed perceptions of what can bring us happiness. We thus end up investing our energy and our lives to the purpose of claiming these false sources of gratification.

In this article, I want to further discuss why our expectations are so often misled. Why do we make such inaccurate predictions about our happiness?

1.We first ought to comprehend how our mind estimates affairs: not as individual conditions, but on the basis of comparison.

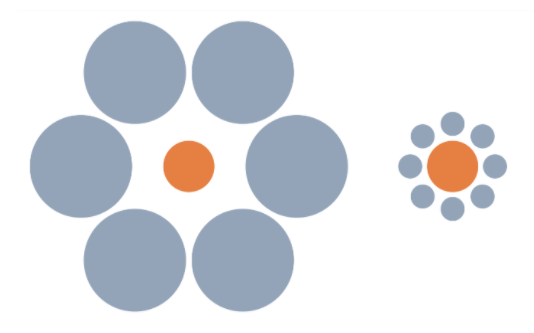

For instance, let’s examine the figure below, commonly referred to as the Ebbinghaus illusion.

The illusion makes us perceive the two orange circles as inequivalent in size. Specifically, our brain registers the circle on the right as the larger of the two. In reality, the two figures are identical, as one can notice by removing the grey circles. The latter are the barriers inhibiting us from ‘accurately’ seeing the central orange circles. We can only conceive them in relation to one another.

Unfortunately, this is how we conceive everything in life: in comparison to other stimuli with which we come into contact. This results in our judgement being misguided, making us lose sight of what it is we truly desire. We evaluate the events taking place in our lives with reference to other people’s experiences. And we oftentimes judge ourselves on the same basis, leading to the expected emotional distress.

Medvec and associates have conducted a relevant study (1975), examining athletes who have won medals, and their subsequent level of happiness. Such studies have showcased that gold medalists usually become the reference point for the rest of the herd. To be precise, there is a disparity in the emotional response by silver and bronze medalists, between learning they have won a medal, and stepping on the pedestal alongside their peers. The ones most challenged are silver medalists, whose levels of happiness are lower in comparison to bronze medalists, and further diminish when stepping on the pedestal. They fail to come to the realization that they have distinguished themselves amongst so many athletes. What apparently troubles them is the missed opportunity at gold, which leads to consequent disappointment. In contrast, bronze medalists consistently state higher levels of happiness, possibly content with the thought they made it to the top three.

There is an abundance of such examples in our everyday lives. Whether talking about the search for the highest grades, the perfect body, or the incomparable wage, we tend to religiously compare. For instance, the manner in which we evaluate a potential job, largely relates to how the wage of that job lines up against our current salary. Research indicates that we compare the present to the past and to our yearnings. This is our individual point of reference. In one such study conducted in the United States, participants were asked what salary would be required for them to be happy. The results proved astonishingly consistent: for every dollar they currently earn, they would need an additional $1.40. For instance, someone earning $30,000 on a yearly basis, would be expected to describe $50,000 as an ideal salary. Nevertheless, someone earning $100,000 would not see $50,000 under the same light, and would thus state that $250,000 is their desired salary, which is an additional $2.50 to every dollar they currently make. This number continuously augments. In other words: we are never satisfied.

Despite that, the most crucial and frustrating reference point, and the one that potentially influences us the most, is not our individual one. Our reference is where other people stand; our social connections.

In fact, we are more interested in how we compare against other people, rather than in our own personal level of happiness. This is ultimately how we estimate our individual value. We make attempts at ‘ranking’ ourselves in relation to others, no matter what it is we do.

In 1996, Clark and Oswald from the Economics Department of Warrick University completed a study involving 5,000 British workers from a variety of professional backgrounds. One of their core findings was that personal satisfaction enjoyed due to professional duties is diminished when one’s peers’ wages are increased. In other words, when you feel you are in a financially disadvantaged position compared to your people of reference, you like your job less. Therefore, if your colleagues are compensated more than you are, you are more likely to be dissatisfied with your position, even if your quality of life you can buy with your salary has not been disturbed.

Clark and Oswald’s research also included unemployed participants. It showed that when the unemployed individual resides among working people, the former is heavily impacted. However, in an area where multiple of their peers are unemployed, they feel more positive, even though the overall employment rate around them is so low.

The same thing happens when someone who is overweight lives among overweight people, someone rich lives among rich people, and someone smart lives among smart people.Consequently, we are so susceptible to social comparisons, that our emotional state is directly influenced by the conditions people around us experience.

This becomes even more acute when inserting into the equation the question of what a logical social comparison is. Many people’s points of reference are heavily charged by stimuli they regularly receive. Research has suggested that people who consistently watch television are exposed to higher wages and wealth, extreme beauty standards, and perfect romance scenarios. All these catalysts make people feel like they have gotten the short end of the stick, which in turn incites sadness. The same could be stated for social media like Facebook, or Instagram, where every user shares their best moments – and comparing with them can be devastating, discarding what would be a more reasonable point of reference.

More specifically, Vogel and associates have provided evidence pointing out a significant negative correlation between self-esteem and social media usage by younger individuals (2014). To put it plainly, the more time you spend on Facebook, the lower your self-esteem is likely to be.

At this point, it could be argued that it is rather people with low esteem that spend the most time on social media, and not the other way around. Nevertheless, on a secondary study, participants were provided with artificial posts, which depicted both people having a pleasant and an unpleasant time. Social comparison with the former always resulted in the reduction of their stated self-esteem, believing the people involved in the posts were better than them. Comparing themselves to the individuals having an unpleasant time did not, however, lead to a similarly significant emotional impact. It did not increase their self-esteem.

The research outlined above showcases that social media, and all the issues that arise due to our set points of reference have an apparent detrimental effect on our internal state. This knowledge verifies that the quickest and perhaps the most effective action you can take to begin guiding yourself towards happiness is to switch off the TV, and log out of social media. Chances are they are not helping you.

2. The adaptability of our mind: why it can prevent long-lasting happiness

The same way our eyes adapt to bright lights, or the lack thereof, our mind becomes acquainted with whatever surrounds us. This adjustment process functions perfectly both with positive and negative events in life, such that the feelings these events bring forth gradually fade out in time.

This is what makes all the extraordinary things we desire less extraordinary when we finally acquire them. Thus, within a mean of two years:

- The happiness you felt when you first got into University has downsized, because you have gotten used to that idea and are now seeking your next objective.

- The happiness you felt the day of your wedding has decreased, because you became used to having this new person in your life.

- The happiness of a raise has faded away, and you now wait for the next one.

Science now suggests that we tend to overestimate the emotional impact of certain events, in terms of their intensity, and of their duration. We believe life will be improved if we obtain what we desire, and that the impact of our new achievement will last longer than it actually does. But the inverse can apply as well. We, thus, can believe that our lives will be significantly worsened if something bad happens, and that the effect of such event will last forever. Our predictions, however, are not validated by the scientific data.

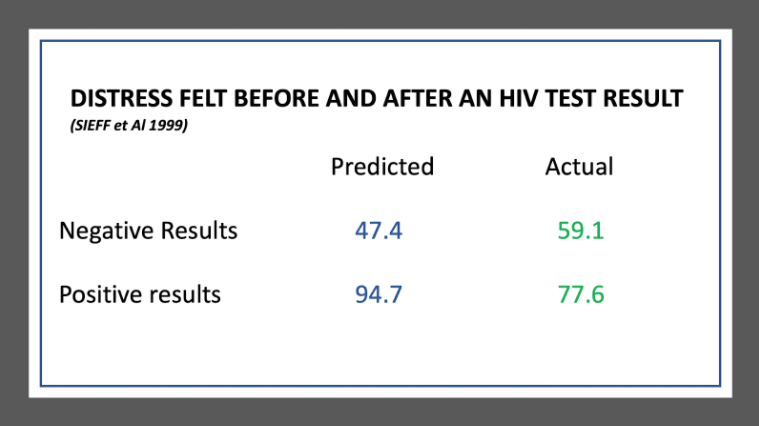

For instance, in 1999, Sieff and his associates explored the disparity between the predictions people made about how they would feel receiving their HIV test results, and how they actually felt. The scale captures emotional distress, with a maximum of 100 degrees. On the table below, you can see how these predictions are far from reality.

Negative tests entail a lower predicted emotional response than the one actually experienced, while positive tests show a higher predicted emotional response than the one experienced. In the latter case, negative emotions are to be expected, considering these participants tested positive for HIV. Nevertheless, while they had predicted an increased emotional distress, in reality what they truly felt was of a significantly lower magnitude. Participants who tested negative were not as relieved as initially predicted either.

You might think that we are inaccurate in making such predictions because we rarely have to make them. We usually do not experience neither too positive, not too negative events. In countering this notion, consider the information below.

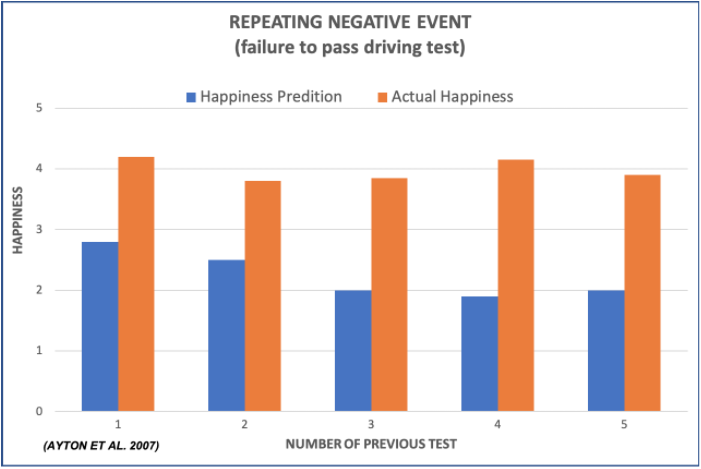

Ayton and associates (2007) collected data about predicted and actual emotional response to receiving grades for young participants who took multiple driving exams and failed. The bar chart below indicates that while participants were expecting their happiness levels to significantly diminish if they did not pass the exam, that was not later validated. Not even in cases where they had to repeatedly re-take the exam. It is visibly obvious that our mind tends to forget past experiences, and thus makes predictions similar to our initial ones. This ultimately comes to show just how resilient we are, but also how unprepared to realize that.

Dan Gilbert and his team discovered that negative predictions about our emotional response to certain events are induced by our absolute concentration on the given event. Put differently, we solely focus on a singular moment, and lose sight of everything else. Say you are facing the aftermath of a separation. You will not spend day and night mourning for losing your lover; at least not forever. Your friends will take you out, you will take a few deep breaths, perhaps even scroll over some puppy pictures on the internet, and eventually you will move on. You do not have to be entrapped within the confines of the event that occurred. In times of distress, your defense mechanisms start operating, and you are more influenced by those mechanisms than you perhaps realize. The collection of these mechanisms is what we refer to as our psychological immune system, and it empowers us to adjust to negative conditions.

In conclusion, we have discussed how our mind processes affairs not in terms of their individual merit, but in comparison to other stimuli. As such, our predictions about what will offer us emotional gratification and how long that gratification will last, are usually inaccurate. The effect that both negative and positive events have in our lives is less significant, and commonly has a short life-span. We might not realize it, but we are impressively resilient.

Only one question persists: how can we terminate these games that our mind plays and that have the potential of bringing negative emotions to the forefront? What are the habits that you can adopt right now in order to bypass these hindering brain functions?

For all that, make sure to read next month’s newsletter.